The story of the Earth’s evolution, unfolding over a vast span of millennia, begins with an empty stage. Although the fabric of the Earth’s crust is some 4,600 million years old, the first stirrings of life did not disturb the barren expanses of its surface until about 1,000 million years after its formation. A further 3,000 million years were to elapse before the appearance of creatures that left recognizable fossil evidence.

The timescale of evolution.

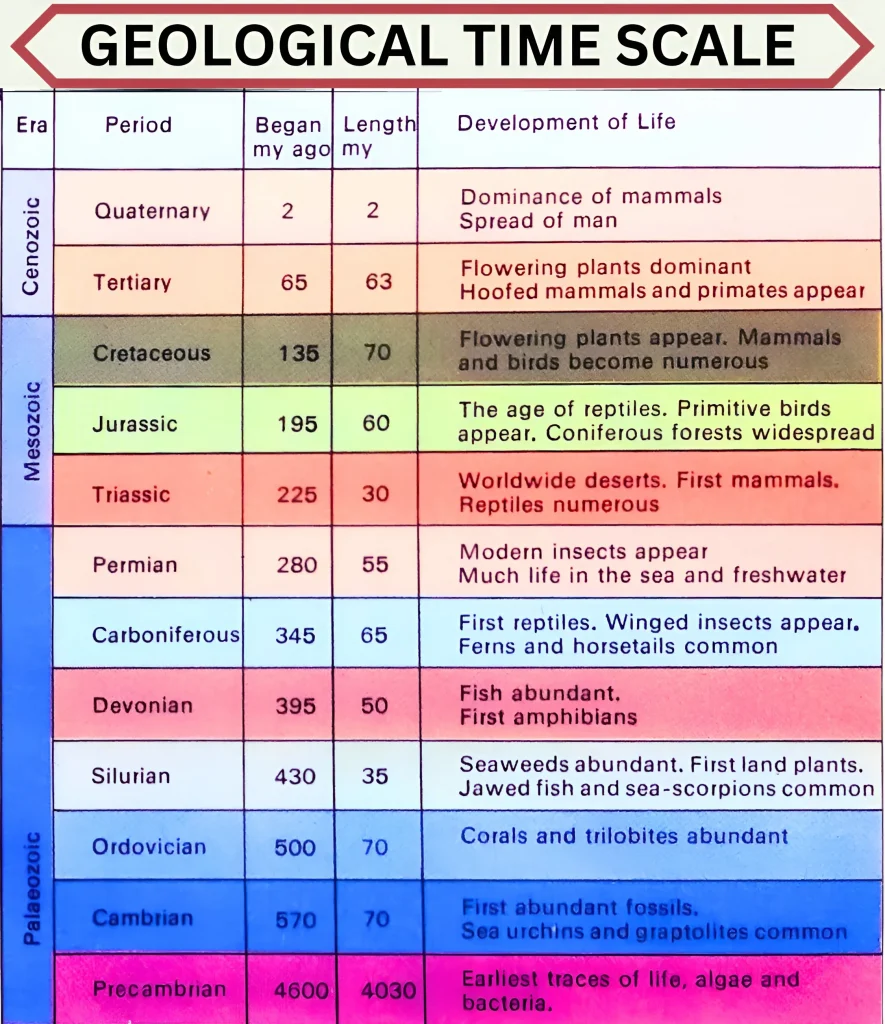

From their studies of the Earth’s crust, scientists have distinguished three broad geological eras following the long awakening of the Precambrian. They are the Paleozoic (Greek for “ancient life”), Mesozoic (“middle life”), and Cenozoic (“recent life”).

Each is divided into richly diverse periods, and the Cenozoic, spanning about 65 million years, is further subdivided into epochs. Although the origin of life remains a subject for continuing speculation, it was not until the publication of Darwin’s theory of evolution in 1859 that the argument became the province of scientists as well as philosophers.

Modern paleontologists, aided by technology, have confirmed much of his intelligent guesswork by accurate measurement. Great advances, in particular, have been made in the dating of fossil remains.

The recent discovery of the basic genetic material known as deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) has also increased our understanding of two contrasting mechanisms in evolution. One is the way in which species reproduce themselves faithfully, and the other is the process by which new species of animals and plants come into being. The second involves mutation — minute changes to DNA instructions.

During the earliest period, the Precambrian, the Earth was devoid of life for possibly 4,000 million years. However, although there was no oxygen in the atmosphere, the primeval oceans of that desert world already contained the basic constituents of life.

Primitive organic structures such as bacteria and algae were the first to evolve, and their appearance, more than 3,500 million years ago, was the turning point in the history of the Earth, which had become inhabited.

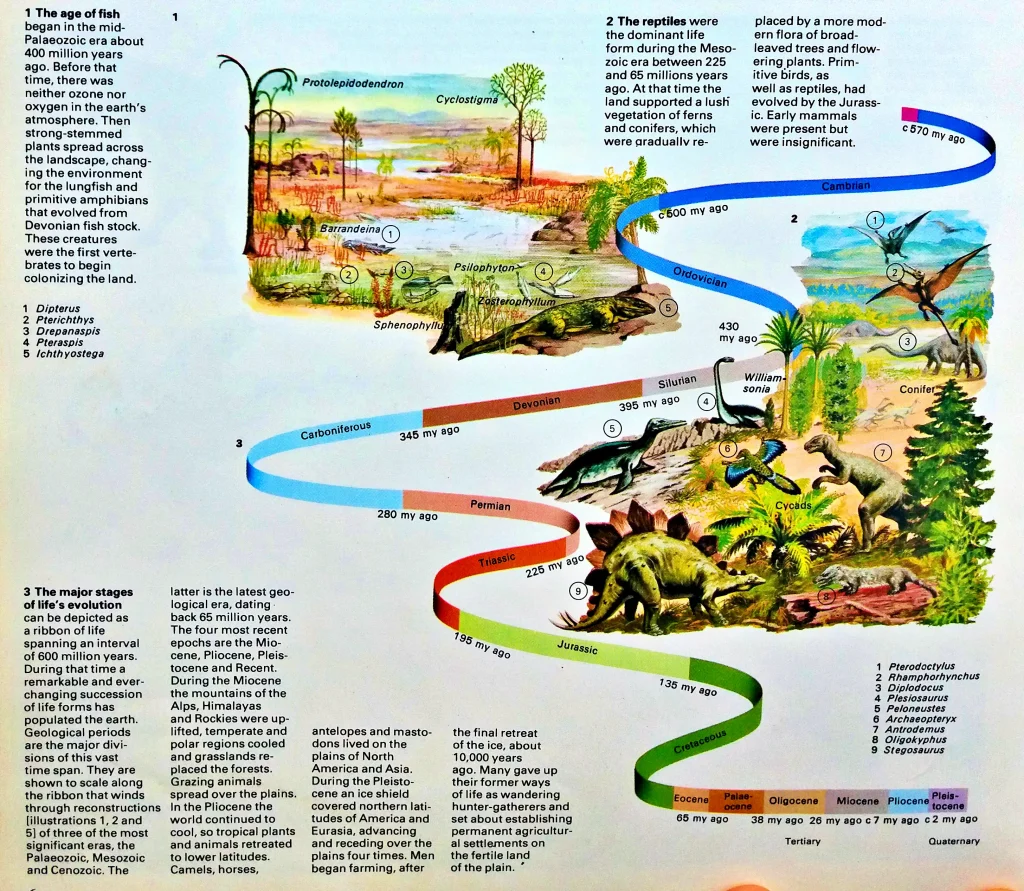

Following on from early soft-bodied forms, the shelled creatures of the Cambrian period provided the earliest yield of fossil remains, the most numerous being the many-legged trilobites. It was not until the Ordovician period that the first fish-like vertebrates began to appear.

By the time that jawed fish had evolved, towards the end of the Silurian, marine plants were reaching the shore.

The first land dwellers

At last, as the Devonian period opened, there were living things on land as well as in the sea. This was a time of great topographical change. The crust of the Earth rose and fell, throwing up huge mountain ranges, and the oceans advanced and receded several times, exposing mud that was rich in organic materials.

As lush vegetation grew up to carpet bare rock, the first insects appeared. Then came the first vertebrate to emerge from the sea the lungfish and, by the end of the Devonian, amphibians had evolved.

In the Carboniferous period, the reptiles developed. These new animals had better brains and physical systems than the amphibians from which they had evolved and, furthermore, did not have to return to water to lay their eggs.

The cotylosaurs, or stem reptiles, were a simple group that gave rise to many new forms, the most significant development from them being the mammal-like reptiles that sprang up in the Permian. These finally evolved into the first mammal desert conditions of the Triassic.

Curiously, it was the thecodonts small in size, but one of the most successful reptile groups — that evolved into some of the biggest creatures that ever lived, the dinosaurs. Not all members of the vast dinosaur family were giants, however: the meat-eating Podokesaurus, for example, was only the size of a chicken.

But among the long-necked vegetarians of the late Jurassic and early Cretaceous periods were the 25m (82ft) long Diplodocus, and Brachiosaurus which, weighing more than 50 tonnes, was the heaviest land animal of any era.

Recent theories tend to suggest that the dinosaurs and other large reptiles, including the flying pterosaurs, were warm-blooded and more like mammals than reptiles in behavior.

Certainly, they gave rise to warm-blooded descendants, such as birds, which may have evolved directly from one of the two orders of dinosaurs. The first mammals in this age reptiles were possibly monotremes egg-laying mammals.

The End of reptile dominance

Towards the end of the Mesozoic era, sweeping geological changes altered the face of the earth. Gradually the single large continent had been breaking up into separate land masses [Key]. But now the slow-moving drama of evolution suffered a bewildering

change of cast: for no apparent reason, the dinosaurs and their bizarre relatives, the great swimming and flying reptiles, died out. With their demise came the birth of a new era, the Cenozoic, and the way became clear for the proliferation of mammals.

The catalog of mammalian life, studded with such oddities as the first horse the size of a fox — was enlivened above all by the arrival, a million years ago, of Homoerectus, the first man. It had taken more than 4,000 million years for him to appear.

References Books

The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs” by Steve Brusatte, “The Story of Earth” by Robert M. Hazen, and “The Origin of Species” by Charles Darwin. Reading books on this topic can provide a more in-depth understanding of the history of the planet and its inhabitants.